Protection vital in donkey work

Editor's note: As protection of the planet's flora, fauna and resources becomes increasingly important, China Daily is publishing a series of stories to illustrate the country's commitment to safeguarding the natural world.

Bi Junhuai, deputy dean of the College of Life Sciences and Technology at Inner Mongolia Normal University and author of the book Research on the Mongolian Wild Donkey.

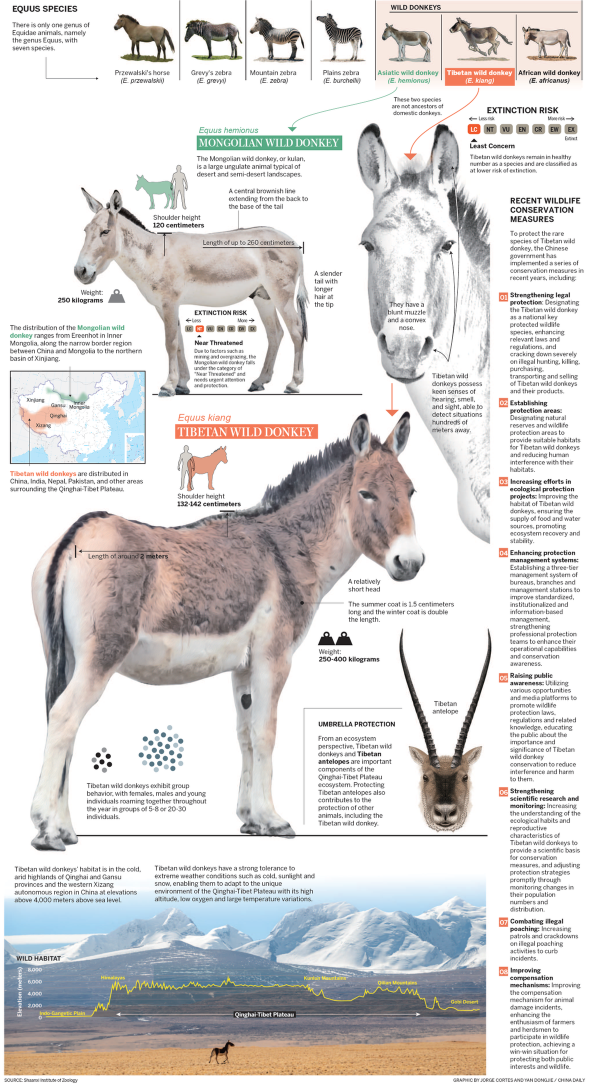

The population of Mongolian wild donkeys, or kulan, within China is primarily distributed in the Xinjiang Uygur and Inner Mongolia autonomous regions. Over the past two years, I have conducted extensive surveys in the Kalamaili National Nature Reserve in Xinjiang and estimate that the population of Mongolian wild donkeys in this area ranges between 4,000 and 5,000 individuals.

In Inner Mongolia, the number is relatively smaller, especially during the summer. This is due to their migration between Mongolia and Inner Mongolia, moving southward in winter and northward in summer. Ten years ago, the summer population of the donkeys in Inner Mongolia was about 100. In recent years, their numbers have increased, reaching between 200 and 300.

The Mongolian wild donkey is classified as a first-class national protected animal in China. This designation highlights both their scarcity and the significant challenges they face in their habitat, necessitating urgent human attention and protection.

They inhabit desert and semi-desert regions, requiring vast open spaces, adequate food resources and water. However, grasslands in Inner Mongolia have become extensively fragmented, with over 80 percent of the grasslands allocated to individuals. To protect their pastures, herders have built fences, which severely restrict the free movement and survival of the donkeys.

Fences not only hinder the migration of the donkeys but also pose a direct threat to their safety. Many have been injured or even killed while attempting to cross these barriers.

Last year, while driving over 30 kilometers along the China-Mongolia border, I saw 14 Mongolian gazelles that had died entangled in fences. It was heartbreaking. This year, social media has shown videos of herders rescuing Mongolian wild donkeys trapped in fences.

To protect the donkeys and other ungulates, I have been advocating for restrictions on grassland fencing. In 2008, I undertook a research project for the Inner Mongolia Party Committee and proposed the establishment of a long-term mechanism for grassland ecological security. This proposal was adopted by the State Council in 2010, leading to the implementation of a long-term incentive mechanism for grassland ecological security.

Ungulates are a vital component of the grassland ecosystem, and changes in their populations can have unpredictable long-term ecological impacts. In my efforts to promote the protection of Mongolian wild donkeys and other ungulates, I have interacted with many herders who actually have a deep affection for the Mongolian wild donkey.

On one occasion, I suggested to a herder that if he liked the Mongolian wild donkey and wanted them to visit his pasture, he could leave some water in the trough after watering his livestock. The Mongolian wild donkeys would come if they found water there, and over time, they might decide to stay. He followed this advice, and now, a family of Mongolian wild donkeys lives in that area.

Protecting wildlife is not overly complicated; sometimes, we simply don't realize the impact our actions have on them. Therefore, awareness is a crucial element in conservation efforts.

Bi Junhuai talked to Yan Dongjie and Yuan Hui.

Contact the writers at yandongjie@chinadaily.com.cn